Currently reading

I Am Pilgrim: A Thriller

Legends of King Arthur: Idylls of the King

The Norton Anthology of Poetry

The Beautifull Cassandra (Little Black Classics #33)

Jane Austen was a pre-consumerist writer who cared not for world-building or owning things, but instead of people's countenances, beauty and humour. She lived from the 18th to the 19th Century in England and gained little fame in her lifetime for her works, having published them originally anonymously.

Jane Austen was a pre-consumerist writer who cared not for world-building or owning things, but instead of people's countenances, beauty and humour. She lived from the 18th to the 19th Century in England and gained little fame in her lifetime for her works, having published them originally anonymously.I much prefer her earlier works. The Beautifull Cassandra is taken from Love and Freindship and Other Writings, both of which are examples of her juvenalia: things she wrote as a teenager and younger woman to entertain her family.

Despite the glaring spelling mistakes (I utterly adore Penguin for leaving them in) Austen was obviously a wonderful storyteller from an early age. I prefer her juvenalia because she was not so wholly concerned with love at that time. Austen has wonderful books, but they, for the most part, follow the same plot and storyline and the difference in tone in these earlier pieces is wonderful.

She wrote of drunkenness, debauchery and murder. She wrote of theft, audacity and the marvel of not necessarily doing as one should in accordance to how others view you should. There is a naivety to these writings that are not found in her later works, but there is also a wider outlook on life that I think perhaps died a little within her as she grew older.

A Hippo Banquet (Little Black Classics #32)

Mary Kingsley was an 19th Century English scientific writer and explorer. She wrote two books about her journeys through Africa and helped to change Europe's view of the African cultures and British Imperialism.

Mary Kingsley was an 19th Century English scientific writer and explorer. She wrote two books about her journeys through Africa and helped to change Europe's view of the African cultures and British Imperialism.I had never heard of Mary Kingsley before I picked this book up and I think that is the greatest tragedy. How many men have I heard of who travelled the world, how many men I have read who spoke of daring deeds and exotic places. And here we have a woman who travelled alone and of her own interest to a land that, at the time, appeared to be wild and definitely not a place for a Victorian lady.

She has a wonderful turn of phrase and although she often reminds us that she is, of course, a woman, everything she does is everything an explorer should do. She fought off two Leopards as they fought dogs and she stumbled upon almost every creature known to man by accident, but did not run in fear but instead stood and watched. She did not take any crap from any man, whether or not they wore a British Military Uniform or a simple loincloth about his groin.

And, despite what we may think of the Victorian period, she was greatly received by her male contemporaries, but she did not enjoy the label of being a "new woman". She was not concerned with Feminism, instead she concerned herself with her own well-being, science and the preservation of African culture. She died of Typhoid whilst serving a nurse during the Second Boer War. She was not a woman, a new woman or a man, she was simply a scientist and writer; a Human Being.

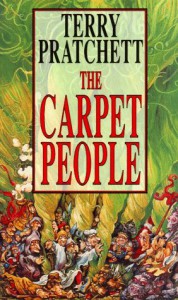

The Carpet People

Before Discworld there were The Carpet People...

Before Discworld there were The Carpet People...This was Terry's first novel and, well, you can sort of tell. It is still wonderfully written and there is the trademark humour he has so wonderfully carved out as his own, but it was definitely not his best. There were ideas and characters and the imagination that can all be found somewhere in Discworld, so if you've read those you'll feel like you're tucked up in a familiar duvet. And if you've read those, you'll be so in love with Terry you won't mind that at all.

It is written well, as previously said, and the pace was so quick I couldn't often keep up, but the humour is so forced sometimes it definitely brings you back down to the reality that this is not a Discworld and not a good one. The imagination of creating a tiny race of people that live in the deepest, darkest parts of a carpet is wonderful, but as with a lot of fantasy I had trouble with getting behind the mix of Real-World terms and Made-Up-World terms. Most fantasy places have some form of cow or horse and a lot of fantasy books will make up a new word for this animal, even though it's obviously a cow or a horse, because what you're actually reading is a (use your imagination) translation of this story from it's original language (the Made-Up-World language) in to English. So even if it's not called a horse there, it will be called a horse in the book. In terms of The Carpet People the mix of Real-World and Made-Up-World creature names was annoying and confusing.

Song of the Sea Maid

Goodness this was the most boring and plotless book I've read in such a long while. The beginning was rather intriguing with Dawnay (a nameless street urchin to begin with) losing her brother to press-ganging sailors and finding herself in an orphanage. Sadly, the story continues at a snail's pace as we have to sit and listen to Dawnay telling us about every single little thing she does at the orphanage, most of which could be conveyed in one sentence alone; I felt as if they author was treating me as being a little ignorant at this point. If the book had begun 70 pages in, with the use of flashbacks or conversations to Dawnay's past, perhaps it could have found itself more.

Goodness this was the most boring and plotless book I've read in such a long while. The beginning was rather intriguing with Dawnay (a nameless street urchin to begin with) losing her brother to press-ganging sailors and finding herself in an orphanage. Sadly, the story continues at a snail's pace as we have to sit and listen to Dawnay telling us about every single little thing she does at the orphanage, most of which could be conveyed in one sentence alone; I felt as if they author was treating me as being a little ignorant at this point. If the book had begun 70 pages in, with the use of flashbacks or conversations to Dawnay's past, perhaps it could have found itself more.The writing style was also rather cumbersome. I do dislike first person narrative rather intensely, so perhaps this has clouded my judgement slightly, but Dawnay's tone of voice never changes throughout her life, despite it starting when she is approximately three years old. She is always so intelligent and curious and hot-headed, from childhood to adulthood and it never changes. It's also written in an odd sort of present tense, which made it feel too distant for me to really get a grip on the (very slim) happenings. There is an attempt to write in the old style, but I can't help but think it would have been rather beautiful if written in third-person past tense. Having said that, writing is nothing but experimentation and I cannot fault the author for trying. If we did not try where would we be?

I actually found the plot to be eventually quite interesting. However, for only three or so pages was there anything particularly adventurous happening, wherein previously we were simply being relayed certain things and feelings by Dawnay, and none of it worth particularly anything at all. It is simply a following of her life and though there is a possibility of it becoming great, it only ends in something as mundane as her narrative.

The caves that Dawnay finds were thought-provoking, as was the fact that she was determined to be a female scientist in a time when this was utterly (but not completely) unheard of. However, the constant barrage of reminders of how ill-treated women were in this time was so utterly demoralising and Dawnay's inability to even pretend to be an Elizabethan woman made the whole book disjointed. I also wish to speak of the ending, because I found it to be utterly infuriating. Dawnay becomes an accidental mother and a make-shift wife and instead of pursuing her dreams of being perhaps the first female scientist to make an exceptional contribution to the world she retires to a quiet place to work quietly. I find this kind of Feminist approach extremely upsetting, because there is an underlying tone that women are mothers and wives first and everything else second. This is utterly banal and I dislike it intensely: woman are mothers and everything else all at once and the fact that she did not push her findings to be published in her own name (or even under a male pseudonym?) was completely detrimental to the whole tone and point of the novel. All her life Dawnay had been pushing the boundaries set down by men and women as to what women can and cannot do and when the time comes for her to be something exceptional she backs out. I found that to be entirely contradictory and, in a word, pathetic. I lost all respect I may have gained for Dawnay at that point.

The rest of the characters felt only as that: characters for Dawnay to interact with. Without them her life would probably have turned out exactly the same. I cannot fathom the point of the book as, as a historical novel, it barely represents anything extraordinary that we do not already know. As a book for escapism there was little world-building and, although it isn't difficult to imagine the caves and 18th Century England that Dawnay traverses, there is little else to spark the imagination further.

There are some references to books in the comments at the end that helped shape the book and they seemed interesting as further reading, but I cannot find anything else positive to speak of.

The Unadulterated Cat

Kind of an odd book until you really think about it. Terry Pratchett is a master of humour but this book lacks it, somewhat. Maybe not actual humour itself, but the amount of it you find elsewhere.

Kind of an odd book until you really think about it. Terry Pratchett is a master of humour but this book lacks it, somewhat. Maybe not actual humour itself, but the amount of it you find elsewhere.I dislike cats though not enough to do anything about it but even I can see their wonderful attributes as described here. I think you'd need to love cats or Terry Pratchett to really understand this book. It is all founded on truth which means it's all a pack of lies, though funny.

The Tell-Tale Heart

Edgar Allen Poe was an American 19th Century poet and writer, best known for his macabre and haunting short stories and poetry, his most famous being The Raven. This Little Black Classic contains three of his short stories, including the well-known The Fall of the House of Usher.

Edgar Allen Poe was an American 19th Century poet and writer, best known for his macabre and haunting short stories and poetry, his most famous being The Raven. This Little Black Classic contains three of his short stories, including the well-known The Fall of the House of Usher.As a well-rounded reader I have obviously heard of Edgar Allen Poe-in fact he is one of the few writers most people have heard of, even those who do not read-but I had never read anything by him. His genre and medium do not interest me but I am always intrigued by classics.

I was quite disappointed, however. The first tale was utterly boring (so much so I cannot remember it's name), though I can see how it could have been mysterious and frightening to the Victorian reader. The Fall of the House of Usher was a much better attempt, but even then it was not frightening nor particularly macabre. And the latter followed the suite of the first.

He does have a good sense of mystery and his writing style is quite well, so I'm sure I will try something more of his.

Incubust

Follow this link to read a very, very short story written by Terry Pratchett in 1988 for a Birmingham University project called Drabble. It's only 12 lines long, but it is extremely funny.

Follow this link to read a very, very short story written by Terry Pratchett in 1988 for a Birmingham University project called Drabble. It's only 12 lines long, but it is extremely funny.Also features in A Blink of the Screen.

The Terrors of the Night (Little Black Classics #30)

Thomas Nashe was a 16th Century English playwright and poet, and is considered as the greatest Elizabethan Pamphleteer and was an early purveyor of erotic poetry. He is most famous for his work Summer's Last Will and Testament and The Unfortunate Traveller.

Thomas Nashe was a 16th Century English playwright and poet, and is considered as the greatest Elizabethan Pamphleteer and was an early purveyor of erotic poetry. He is most famous for his work Summer's Last Will and Testament and The Unfortunate Traveller.The Terrors of the Night is the 30th Little Black Classic and it has thus far been the worst. I'm loath to even give it any stars at all as it was terrible written, confusing and extremely misogynistic. Whilst I can tolerate historical religious writings, Nashe is so utterly mind-numbingly boring he cannot even bring me to find anything good about his writing, except perhaps the few references he makes to English folklore and makes a lightly amusing joke about the terribleness of Holland cheese:

"God is my witness, in all this relation I borrow no essential part from stretched-out invention, nor have I one jot abused my informations; only for the recreation of my readers, whom loath to tire with a coarse home-spin tale that should dull them worse than Holland cheese."

There is no flow to his writings; sentences blend in to one another using punctuation which makes the sentence itself around two pages long on average. He has a tendency to ramble and forget what he is speaking of, then return to it several pages later.

I would suggest you skip this LBC completely, but if you're looking to complete your collection, there's really no reason why you should read it.

How We Weep and Laugh at the Same Thing (Little Black Classics #29)

Michel de Montaigne was a 16th Century French Renaissance philosopher and was the one of foremost essayists and contributed to making essays a popular literary genre.

Michel de Montaigne was a 16th Century French Renaissance philosopher and was the one of foremost essayists and contributed to making essays a popular literary genre. How We Weep and Laugh at the Same Thing contains 6 short essays concerning philosophical contradictions, the most prevalent being that words are useless and actions are the only worthy thing, despite Montaigne being an essayist himself.

There have been a couple of Little Black Classics like this one, but somehow this one seems slow witted and less profound than any other. It was not written particularly well and I found myself having to re-read sentences several times in order to take in what Montaigne was saying. It did not flow quite so well, not did the language or writing style fascinate me.

There were one or two notable ideas, but otherwise Montaigne has nothing particular to say that hadn't already been said, and better, but someone else.

Ugly People Beautiful Hearts

Marlen Komar got in touch with me and asked if I would review her book of poetry, Ugly People Beautiful Hearts. The first reason I said yes was because I am re-discovering poetry and wish to devour as much as I can. The second reason was because of the title and the cover: it sounded intriguing and lovely, yet somehow at the same time there seemed a dark edge to it. The third reason is because it was free. Sorry, but I'm from Yorkshire.

Marlen Komar got in touch with me and asked if I would review her book of poetry, Ugly People Beautiful Hearts. The first reason I said yes was because I am re-discovering poetry and wish to devour as much as I can. The second reason was because of the title and the cover: it sounded intriguing and lovely, yet somehow at the same time there seemed a dark edge to it. The third reason is because it was free. Sorry, but I'm from Yorkshire.I am fairly new to poetry: by that I don't mean I've only just discovered it exists, but that I have just begun to read it for pleasure. Previously it would always be in an academic environment and that means analysis. I have discovered that I loath nothing more than analysing poetry, though I truly love analysing novels. The difference is how you feel it.

"My poems tell a short story in 70 poems how it feels to experience love in all its stages. How it feels to lose it, to gain it, to miss it, and to happily suffer for it. I tell a story of finding happiness and finding loss, and how all of that is a beautiful part of the human experience." (Marlen, in her email to me).

I prefer to read my poetry out loud. Marlen's poetry is not necessarily built for this, so I re-read it in my mind and found it flowed better that way. I find that this is difficult to review and rate for several reasons; one being I am limited in poetry to really compare and two being that it broke all of the poetry rules I know.

Ugly People Beautiful Hearts is written in free-form with little structure and, as far as I can tell, no rhymes. To my untrained eye, this is blasphemy against the Rules of Poetry, but it opened my eyes to what poetry truly is. At first I was surprised, shocked even, but as I got in to it I found that free-form poetry is something truly wonderful and Marlen does it so well. It actually made me realise that poetry may actually be something I myself could try, having previously always felt so restricted with the Rules and Regulations of Proper Poetry.

"You and your light, my dear, have changed the lives of many, many people. More than you'd think to understand." ('But God, You. Just All of You.')

The poems, as Marlen described, are about love, but not the kind of love that you usually read about in novels. It is the kind of love that hurts you deeply, but with a kind of hurt that is wonderful and beautiful to feel. It is the kind of love that really hurts, and never stops hurting, in a terrible and painful way. It is every kind of love imaginable.

Marlen's writing is at once beautiful and pained. Occasionally I found it frustrating, both because of my pre-conceived notion of what poetry should be, but also because there was often a repetition that lacked depth (and there were also too many poems that started with 'And'.) However, writing all over that frustration was the feeling that reverberated through the words: it was as if Marlen was there with me, speaking these words to me even though they were being directed to whomever she loves and loved.

"The scratches of a finished record, it's cracking silence patient as your lips move across mine. As you convince me to think about you tomorrow." ('A Tally of Treasures.')

There were moments of pretentiousness, but I have yet to come across a poet (and indeed very few writers) who did not indulge in pretence once in a while. It often came in tandem with the repetition so it was easily washed over. (As a side, it would have been lovely if each poem was on its own page in the Kindle, but that's just me.)

There were many wonderful moments that I call Hector Moments or Presents Moments (that's a long story, though: pronounced pre-sents, not pres-ants): those moments where you read something or see something that just connect with you; things that you might always think about but had no idea other people did, too. Moments where you all of a sudden know what life is all about or, if not that, possibly that you know what you should do next.

"That moment a someone reverts back into a no one and joins back to the crowd of everyone." ('Eyes That Were Once Green'.)

Wordsworth said poetry "should be the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings... recollected in tranquillity" and I do believe Ugly People Beautiful Hearts conforms to that sentiment completely. There is sadness and there is happiness, and they both cannot exist without the other. Pain cannot exist without euphoria; neither can love exist without hatred. How would you know you were in love if you had not felt hatred beforehand?

"It's all so constantly overwhelming, isn't it?" ('The End. In All Senses of the Word.')

The Wife Of Bath (Little Black Classics #28)

Geoffrey Chaucer was an English 14th Century diplomat and philosopher amongst other things, though is best known for being a Poet and writing the Canterbury Tales. The Canterbury Tales were written during the 100 years war and tell of a group of pilgrims on they way to Canterbury Cathedral to visit the shrine of Thomas Beckett, with the prize being a free meal at an inn.

Geoffrey Chaucer was an English 14th Century diplomat and philosopher amongst other things, though is best known for being a Poet and writing the Canterbury Tales. The Canterbury Tales were written during the 100 years war and tell of a group of pilgrims on they way to Canterbury Cathedral to visit the shrine of Thomas Beckett, with the prize being a free meal at an inn. "You say it's torture to endure her pride

And melancholy airs, and more besides.

And if she had a pretty face, old traitor,

You say she's game for any fornicator."

Each Pilgrim has their own prologue and tale, and this one belongs to the Wife of Bath. This Little Black Classic is different to the usual Chaucer books in that this one has been translated to modern-day English, making it the perfect starting point for anyone who is looking to read some Chaucer but hasn't either known where to start or has been put off by the Middle-English language.

"True poverty can find a song to sing.

Juvenal says a pleasant little thing:

"The poor can dance and sing in the relief

Of having nothing that will tempt a thief."

The Wife of Bath's Prologue, as all the pilgrim's prologue do, contains information about the Pilgrim themselves at first, giving you a taste of their countenance and backstory. Then their tale is told, which in this case is an Arthurian tale of a misogynistic knight who, in exchange for his life, must find out what women truly desire. It is a tale that could have been written in this day and age, and it reminds us just how mediaeval our gender equality and ideals really are.

A Slip of the Keyboard: Collected Non-fiction

Sir Terry Pratchett OBE died on the 12th of March, 2015, at the age of 66 from a rare form of Alzheimers. He wrote over 40 novels and was the creator of one of the greatest fictional worlds; Discworld.

Sir Terry Pratchett OBE died on the 12th of March, 2015, at the age of 66 from a rare form of Alzheimers. He wrote over 40 novels and was the creator of one of the greatest fictional worlds; Discworld.When I was 12 I read my first Discworld and I hated it. It was The Colour of Magic and, from memory, the reason I hated it was because it had the word "bastard" on the first few pages. To me now, this is absurd. The first thing I do when I wake up is swear, usually one of the worst ones (ones much worse than "bastard"), and so my memory of this first read is tinged with confusion and humour.

I left them alone for nearly ten years, until a good friend of mine suggested I try them again. I don't recall which one I tried in my second attempt but, after being given almost all the books second-hand by a University friend, I devoured them wholly and without chewing and spat out an unadulterated obsession with the Discworld and Sir Terry himself.

A Slip of the Keyboard includes articles and short-essays that Terry has written, in between writing roughly two novels a year. Much like his Discworld series, they are funny, educational, insightful and very, very Human. The topics covered are as varied as the own man's interests, from Orangutans to hats and from writing and reading science fiction and fantasy to suffering and speaking up about suffering from early-onset Alzheimer's and the right to die with dignity.

Although I love this book, and will love it forever, and will re-read it more than I will re-read any other book, and have gained around thirty new books to add to my to-read pile, it has only gained four stars for the following reasons: one, the sadness I felt whilst reading a great dead man's words was overwhelming, and two, my blithe shelf is for fiction only. This is not fiction, but in heart it is five-star worthy.

It's a sad thing that this man died, but it is greater still that he lived.

The Nightingales are Drunk (Little Black Classics #27)

Hafez was a 14th Century Persian poet whose works are amongst the most popular in modern-day Iran. The nightingales are drunk is a collection of his poetry taken from Faces of Love.

Hafez was a 14th Century Persian poet whose works are amongst the most popular in modern-day Iran. The nightingales are drunk is a collection of his poetry taken from Faces of Love. Hafez likes wine. He likes drinking wine a lot. He revels in speaking to himself as if he were another person and his drinking is much a common problem with his religious practices.

"Speak Hafez! On the world's page trace

Your poems narrative;

The words your pen writes will have life

When you no longer live."

No poem owns a title and the prevalent theme is, indeed, wine. Personally, I found him pretentious and boring, speaking of wine and wine and referring to himself in the third person and speaking of drinking wine and sitting in a wine shop drinking wine. He was repetitive (wine) and his poems just did not roll well off the tongue. I assume this has a little to do with translation, too, but altogether just a pile of tosh.

Dodger's Guide to London

Dodger's Guide to London comes as a companion to the novel Dodger and provides us with a casual look at what life was like for the lower classes of Victorian London.

Dodger's Guide to London comes as a companion to the novel Dodger and provides us with a casual look at what life was like for the lower classes of Victorian London. It's a good place to start if you're looking to start researching Victorian London, as it has some very good references and recommendations for further reading. Paul Kidby provides the wonderful illustrations that always accompanies Terry Pratchett's work, as well as some real-life photographs that do not disappoint in bringing the era close to hand.

It does not contain much humour, though I would suggest this was a child-orientated book, and as such it can get a little boring. In-and-out reading would be best, and definitely it is a referenceesque book as opposed to any other kind. Be wary of the fictional elements that Pratchett provides, as these are not factual and may trip you up. Altogether an interesting read.

The Owl who was Afraid of the Dark

My copy of this book is probably as old as I; it is bashed, bruised, torn and tattered and there is cellotape holding the pages in, as well as some of the pages together as a whole.

My copy of this book is probably as old as I; it is bashed, bruised, torn and tattered and there is cellotape holding the pages in, as well as some of the pages together as a whole.It is, quite delightfully, a wonderful children's tale about a Barn Owl named Plop who is afraid of the dark. He simply hates it, but his mother and father are tired of him always waking them up during the day (when they are, of course, fast asleep) and asking them to feed his never-ending appetite.

"So Plop shut his eyes, took a deep breath, and fell off his branch."

Plop is no good at landing, so he mostly just falls. He visits various people and animals and asks them about the darkness and in turn, they each give him a reason why the darkness is not a foe but instead a friend. It's beautifully written and it's quite a rare thing to come across a children's book that is quite as lovely as this one. Definitely a childhood favourite; definitely.

Of Street Piemen (Little Black Classics #26)

Henry Mayhew was an English Victorian journalist and playwright who actively sought to create an equality amongst the inhabitants of England and a London. Of Street Piemen contains extracts from his book series of newspaper articles London Labour and the London Poor.

Henry Mayhew was an English Victorian journalist and playwright who actively sought to create an equality amongst the inhabitants of England and a London. Of Street Piemen contains extracts from his book series of newspaper articles London Labour and the London Poor. This is an invaluable resource in to the poor of London in the Victorian times. It contains first-hand accounts from those who lived and worked in the city, including some lesser-known occupations such as live bird catchers and sellers. It's quite surprising at times and his journalistic writing style gives the writing a tone that is both educational and agreeable. This LBC also features something which none of the previous ones have, and that's a source guide at the back (none feature introductions or footnotes at all) which gives details of where the extracts come from in relation to his other work.